A common thread found between all alternative folk is our hyper-awareness of ‘being weird’, and it’s all too common that we may feel the need to change.

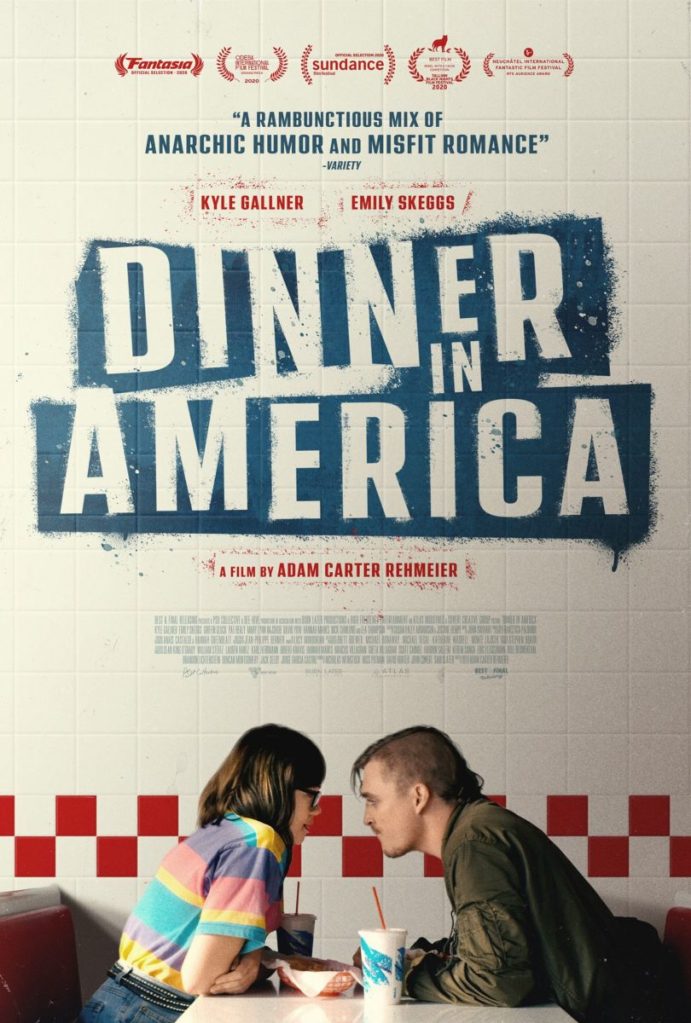

Dinner in America is the perfect guide to show that weird people don’t need to change.

To be weird is to non-conform, and non-conformity is punk, and to be punk is to be free, and to be free is to be unapologetically and authentically your weird self.

☆ Pretty in punk

Dinner in America has reignited in popularity since its 2020 release and my ‘For You Page’ has been inundated with people desiring to be ‘weird’ and quirky.

As someone who has had those labels slapped on my forehead for a while, I thought it worth dissecting the ‘weirdness’ that we see in Dinner in America, through the lens of its most evident theme; punk.

Many facets of life can be categorised as punk, the main three being music, genre, fashion, and lifestyle. These can be interchangeable and cross-over between each other, but it isn’t necessary that someone takes part in more than one for them to be catagorised as ‘punk’.

For example, you could listen to punk music, but not dress ‘punk’. In the same vein; your political ideals could align with anti-authoritarianism and anti-consumerism, but your music taste could be something totally different.

‘Punk’ can also be used to insult someone; a person who is out to cause trouble and not conform. How strange that society disfavours people who openly disobey societal norms in the name of self-expression.

Image Credit: Unsplash

Having an understanding of what punk is and what it relates to helps us have a wider perspective on the characters we see within the film. It also helps us consider the reasons behind the decisions they make.

Simon, portrayed by Kyle Gallner, is the frontman of a punk band. He is hotheaded, has a strong sense of justice (so strong in fact, that it has caused hostile relationships with his family and friends) and has very obscure ways of showing his care for others.

Image Credit: Dinner in America, Dir. Adam Rehmeier

I’ve seen otherwise ‘normal’ people online being scrutinised for wanting to be weird because of this film. It’s incredibly well-documented that weird kids are bullied by those considered more normal – it is literally the biggest plot point in most tv shows and films, so I completely sympathise with the fear that ‘weird girl’ is becoming a niche micro-trend; ‘weird-girl-core’ will now be tinted to fit a more easily-digested aesthetic – ‘i wore odd socks today’ instead of ‘i haven’t taken off my favourite socks in a week’.

Perhaps it’s also a fear that they won’t be caught out and that the ‘true weirdos’ will be left outcasted whilst the posers get to be ‘weird but in a cool way’. The beauty of being outcasted is that there isn’t really a hierarchical system; no weirdo is better than the other.

In the not-so-distant past it is this absurdity that has caused many people to feel unloved, unsupported, and outcasted.

☆ She’s just so different – rejecting manic-pixie-dream girl

Throughout the film, we see Patty (Emily Skeggs) sexually harassed and berated with derogatory language by two ‘jock’ archetypes, to which she sits silently and tries to awkwardly disengage.

It is revealed that Patty quit college at some point, and I think it’s safe to assume it was either due to bullying, or her disability (we know she is on multiple daily medications, but it’s never disclosed what for).

There has been a lot of praise for Patty’s anti-manic-pixie-dream girl portrayal, and Simon’s treatment of her.

The reality of being labelled a ‘manic-pixie-dream girl’ is that your abruptness and ability to call out bullshit is excused because you’re pretty, and unless you can provide emotional development to your male love-interest, or are sexually available to them, you are pretty much redundant. Patty is dismissed often, but not because she is palatable.

Simon does brazenly flirt with Patty but he doesn’t expect her to teach him some sort of life lesson.

Despite the bullying and dismissal, she is still unabashedly herself. She isn’t outwardly punk, she doesn’t dress in all black, studs and spikes – she is colourful, ill-fitting and stripey – but that is punk in itself.

Image Credit: Dinner in America, Dir. Adam Rehmeier

The film is uncomfortable for some viewers because it is very sexual, and it’s explored through out-dated, misogynistic references.

We often see these jocks make unwanted sexual advances towards Patty to degrade her; but she completely reclaims her sexuality through engaging with Simon.

She positively gives consent to him: “you can kiss me now. I want you to.”, and the film doesn’t let us forget the fact that she regularly sends explicit images of herself to her music boyfriend, John Q. Internalised ableism has people believe that disabled people shouldn’t want sex. This film is the antithesis of that.

☆ You need to take it down a notch

There is use of derogatory racial, homophobic and ableist slurs that seem to just be part of the every-day vernacular in this film, and this is your reminder that you do not need to engage with a piece of media, if derogatory language is upsetting. The language is used by white, able-bodied, straight people, to degrade and dehumanise others.

It is not clear when this story is set, however the clothing, lack of mobile phones, and how music is only available through cassette tapes, means we can guess this is set around the late 80’s to early 90’s – making the language somewhat ‘fitting’ of the era.

I touch on this again, but the families we encounter are dreadful, and so use of derogatory language fits that context also, making this film a difficult watch because of it.

☆ Time for dinner!

This film made me want to primal scream. it was CATHARTIC.

Weird people can want sex and spontaneity. Weird people can commit crimes. Weird people can have friends, or have no friends. We can dress however the fuck we want because what is there to lose? Society has already deemed us as outcasts, and that is a freedom in itself; to live by no expectations.

The exploration of the title of the film, Dinner in America, is beautifully executed. Influenced by ‘nuclear family’ ideals and americentric views, the dinner table is the centrepiece to family life. With each dinner scene we see that every family is absolutely rotten to their core: racism, ableism, misogyny, and classism to name but a few dysfunctions; all served up on a gingham tablecloth.

These dysfunctions are handled with a Napoleon Dynamite-esque comedic flair, but simultaneously demolishes our preconceived idea of the American Dream and idyllic American family life.

Image Credit: Dinner in America, Dir. Adam Rehmeier

Reconvening at the dinner table symbolises togetherness, connection and community. We are supposed to feel welcomed and understood, especially with family, and both together and apart Patty and Simon are given no grace – no one accepts their unfaltering authenticity except for each other.

Patty was never expected to change, and Simon never sold-out. Existing in spite of it all.

So I dare ask, would you have a ‘weird’ person at your dinner table? someone who was intellectually disabled? incontinent? lacked a grasp of social cues? no respect for authority? obsessively inquisitive? a pyromaniac?

That common thread we all share, the one where we struggle to accept our weird selves, now has its remedy; Dinner in America is a warped, grossly beautiful guide to acceptance.

Featured Image Credit: Dinner in America, Dir. Adam Rehmeier