Standing among waist-height weeds in the middle of a forest during the height of summer with no maps, no sense of direction and an empty bottle of water, I began to wonder if this was a smart way to spend my day.

I wasn’t alone, at least. Although, my friends were at each other’s throats and the group was splitting apart – all in the quest to find Castlebridge Colliery’s abandoned site.

Most of the time when you tell people you like to explore old buildings, they look at you like you’re crazy. Or they think you’re a vandal. Sometimes, they ask if you’re ghost hunting. Unfortunately, only a few people understand the attraction of urban exploring (urbex).

This lack of understanding from general society is but a pinprick among the feelings of euphoria and adrenaline as you stand inside an abandoned building for the first time. These feelings are vivid in my memory as I recall the first “proper” abandoned building I explored.

The Castlebridge Colliery, just outside of Forest Mill, was formerly part of a coal mining complex.

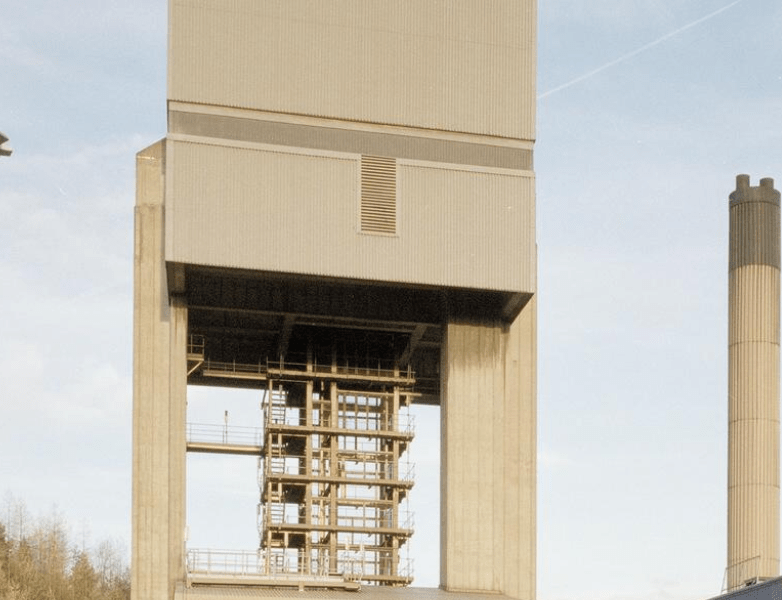

It was part of the Longannet Complex, which operated from 1969 to 2002. The complex mined Upper Hirst coal and directly served Longannet Power Station, contributing more than 10,000 tons of coal each day to the station. Joining Castlebridge as part of this complex were the Bogside, Solsgirth, Castle Hill, and Longannet Mine collieries.

The main building of Castlebridge Colliery. Image Credit: Canmore

Castlebridge Colliery contributed to the success stories of the Longannet Complex. Miners consistently broke productivity records. The complex also claimed to have the longest underground conveyor belt in the world at the time (more than five miles long).

The site was used as a model for modern mining developments throughout the UK.

Eager to see the beauty for ourselves, a small group of friends and I set out on a very unplanned, very reckless journey to the colliery.

With the scorching summer sun beating down on our sweaty and tired faces, a murmur of frustrated bickering infected the group.

Already, the adventure looked like a bust.

Just as another argument was bubbling up I saw the starts of a metal fence hidden within the overgrown vegetation. One tight squeeze later and we were in.

We rushed through the smaller buildings to get to the main attraction – something I would come to sorely regret. I didn’t know what the future had in store for Castlebridge Colliery. I didn’t know that soon after my visit it would be left as a pile of rubble.

I’m not alone in my devastation of derelict sites being destroyed. The urbex community often mourn the loss of sites – either they are destroyed or refurbished. One anonymous urban explorer said: “It’s great either seeing (buildings) before conversion, or before they are lost forever […] sometimes the exploring allows [the] imagination to run wild as you can picture how rooms were used.”

He also told me the interest he had in seeing people’s belongings left in situ as they collect dust – moments frozen in time.

Rubble left behind after the colliery closed. Image Credit: Emma Christie

I suppose not knowing the future tied me to the staff that used to work there. Afterall, Castlebridge Colliery closed rather abruptly.

With the privatisation of the coal mining industry, Scottish Coal (Deep Mine) Limited became owners of the complex. The colliery was the last deep coal mine to be sunk in Scotland.

After the colliery flooded with 17 million gallons of water, which appeared too expensive to repair (an estimated £50m), Castlebridge closed its doors between 2001 and 2002. The day after the flooding, they went into receivership. No other company wanted the site, so it was left to flood further. Subsequently, more than 500 jobs were lost between Longannet and Castlebridge Colliery as the site went into the hands of receivers.

“I remember all the great times working there and [the] absolute great bunch of people to work with. It brings back some great memories,” Alexander Flannagan said in an interview with Deadline News back in 2017.

Pieces of workers’ personalities shone through the rubble when I visited, and you could see fragments of the memories Alexander spoke about. I found small, broken trinkets, handwritten paperwork, several cassette tapes, and an old Star Wars DVD from The Sun. I often wonder if any workers went back to visit it and why so much stuff was left behind.

One of the main rooms littered with graffiti and paperwork. Image Credit: Emma Christie

It was a puzzle I was determined to solve. However, as we continued to rummage around the main buildings, we began to feel watched.

Thankfully, no crazed murderers jumped around a corner and ghosts didn’t start flinging objects across any rooms. No, all we met were people. They were explorers, like us, but actual adults. A brief “hello” and an awkward shuffle later saw us take our separate paths.

Fresh adrenaline coursing through us, my group to tackle the biggest building yet.

Craning my neck upwards at this alien structure had me doubting it was climbable – a rusty, garish staircase swung in awkward angles, twisted and warped by nature. The heart of the building itself was a giant grey cube that looked like a very boring spaceship. It stood apart from the other offices and buildings, taking centre stage as its audience gawked at the glorious stance of the thing.

The way in? A doorway that was three quarters full of rubble which we squeezed through and a pitch-black stairwell that was in severe need of some WD-40.

Most of these memories are fuzzy. The thump thump thump of my heart racing in my ears took my mind’s priority. One wrong step and we were in serious trouble. Yet, we made it, and the reward was worth the deathtrap we endured.

One last squeeze up a tight, encased ladder led us out of the dark and dingy box to the rooftop. Breathing in the fresh air, I allowed my eyes to adjust, and took in the view. Surrounded by dense forest in every direction, we looked down on the one visible road and felt like gods.

Image Credit: Pexels / Jakson Martins

This was a high that I would find myself chasing for years to come.

As we descended the unstable staircase from the Colliery and landed back on firm ground, I took one last sweeping look at the site. It was sunset now and shadows stretched out behind each building, creeping towards the tree line and grasping at the grassy banks. Similar to watching the credits roll after a movie, I recognised dusk as the end of this story.

What I didn’t know was that there would be no sequel.

A few years after our visit the colliery was destroyed, levelled out completely.

After the news of the colliery’s destruction reached me, I put a hold on my adventures. It was the biggest site we could get to – since none of us could drive – and it had been snatched from us. That’s how I felt, anyway. As far as I can tell the land is being used to store natural materials such as grit and stone.

Eventually I found myself with a car but without time to explore more buildings – it was a chapter of my life I decided was inevitably closed: “I’m not a teenager anymore, I have to go to work and university, I have no time for this!” was my justification.

Yet the comfort I felt from exploring such sites drew me back in and my fascination for urbex was slowly revived.

Something new had emerged from this cycle of old behaviours, however. Now, as an adult with unlimited access to the internet, I stumbled across some Urbex Scotland groups on Facebook.

The puzzle morphed from finding out about buildings to seeking answers regarding why these likeminded people explore such hazardous places. I was shocked that so many adults contributed to these pages – people with families, with children, with careers.

Younger me had the ideology instilled in my head that the only people who visited such places

were criminals or troubled youths. I was ecstatic to have these ideas squashed and to become part of a much wider community that was previously unknown to me.

“Having a hobby like this – a distraction from society, brings peace [and the chance to] recharge,” one urbex group member told me.

Another told me that she began exploring during the pandemic as a way for her to spend some time away from everyone else; just her and her little girl.

While many onlookers wish for these sites to be destroyed or repurposed, I pray for them to remain frozen in time and slowly consumed by nature – a thought shared throughout the urbex community. They are not, and won’t ever be, an eyesore to me. Instead, they are a source of excitement, hope, and adventure – a place to feel alive.