The Gothic or the goth subgenre and/or subculture is depicted in much of pop culture as being separate from a distinct environmentalist ethic or even broader ideas of sustainability.

Scholar Charles Crow aptly explains that: “The Gothic mode is superficially associated with ‘women in white gowns fleeing dark mansions’.” That is to say, the goth subculture in the contemporary sphere is viewed through a one-dimensional lens that erases its complexity and in-built analysis of the material world.

This may be in part because the conventions of the genre or subculture are expressly supernatural. Of course, there is an intent focus on ghosts, vampires, and witches – which are neither real nor rooted in the material.

However, upon closer analysis, we can easily see that this pre-conceived notion that goth has no relationship to the real world isn’t true. Writing that expressly connects the materialism of the real world with the surrealism of narrative fiction is part and parcel of the Gothic literary genre.

Image Credit: Pexels / Cottonbro

As will be explained, the inclusion of supernatural elements within the Gothic is demonstrably an exploration of nature and its very own limits in multiple texts and music lyrics. Goth may function as a form of escapism for many, but for some it is a force of rebellion or confrontation with what is real, tangible and concerning.

Goth’s Environmental Tendencies

In Gothic Nature: An Introduction by Elizabeth Parker and Michelle Poland, they outline their tale of ‘two gothic natures’:

“One: You are lost in a wood. Now survive.

Two: The planet you think you live on no longer exists. Now survive.”

The latter seems to apply very heavily to gothic interpretations of nature. The Sisters of Mercy’s Black Planet from the album First Last and Always is a good example of how ecological anxieties can draw out dark fantasises of an all-consuming ecological decline. The song’s lyrics lament a darkness over Europe, as well as its eventual descent into a world (a black planet) full of radiation and acid rain.

Image Credit: The March Violets ‘The Botanic Verses’

The songs fixation of these on both may be a reference to anxieties about war and its existential threat to life on earth. The imagery here conjures up notions of eco-anxiety and anxieties about broader political instability.

Moreover, The March Violets album aptly named The Botanic Verses also leans into ecological themes. The track Grooving in Green is a good example of this; the lyrics seem to call attention to the issue of life and existence itself, taking on an existentialist pathos. The lyrics also tie one’s relationship to nature and thus the ‘other’ in the wake of these existential realisations:

“Walking around she carries a knife,

The last page is missing from the book of her life,

Combing her hair, she talks to the trees,

Oh, it’s another disease.”

Goth and the Gothic clearly have a role to play in shaping perceptions about nature and ecological decline. Of course, there may be other reasons for why people do not typically associate the goth subculture and these ideas. Factors such as the commodification of the subculture by way of gothic fast fashion and the decline of DIY culture may accounted for this. It can be argued that these two developments have been critical in drawing attention away from goth’s more ecological roots.

Gothic fashion has its roots in punk, which was by and large took a DIY and holistic approach to fashion. Upgrading old clothing into something new is rife within the subculture, as well as the use of patches, crochet, metalwork, stitching and handmade jewellery.

Image Credit: Mauro Romero / Pexels

Sometimes, those in the goth scene will engage in intra-communal exchanging of DIY clothes. A “spooky circle of commerce”, as the goth blog Gothic Charm School explains. Regardless, those who practice or are invested in DIY are typically also invested in keeping an item of clothing alive for as long as possible. This is one aspect of goth that is quite nurturing – consideration for the sustainability of an item and its impact on the world.

Manuel Pereira Soares takes Portuguese goths as an example. He explains that goths in the region were especially reliant on DIY culture, due to a distinct absence of subcultural markets and exchange. The absence of these markets nonetheless inspired a type of resilience not as commonly seen today in the more mainstream goth scene.

In this way, goth and its DIY culture still thrive in the absence of pre-made outfits and spaces. This example underscores the ephemerality of the Gothic in literature, art and fashion – its cultural persistence and insistence (however fluctuating) in a world that constantly negates its ideals.

Looking to the Past

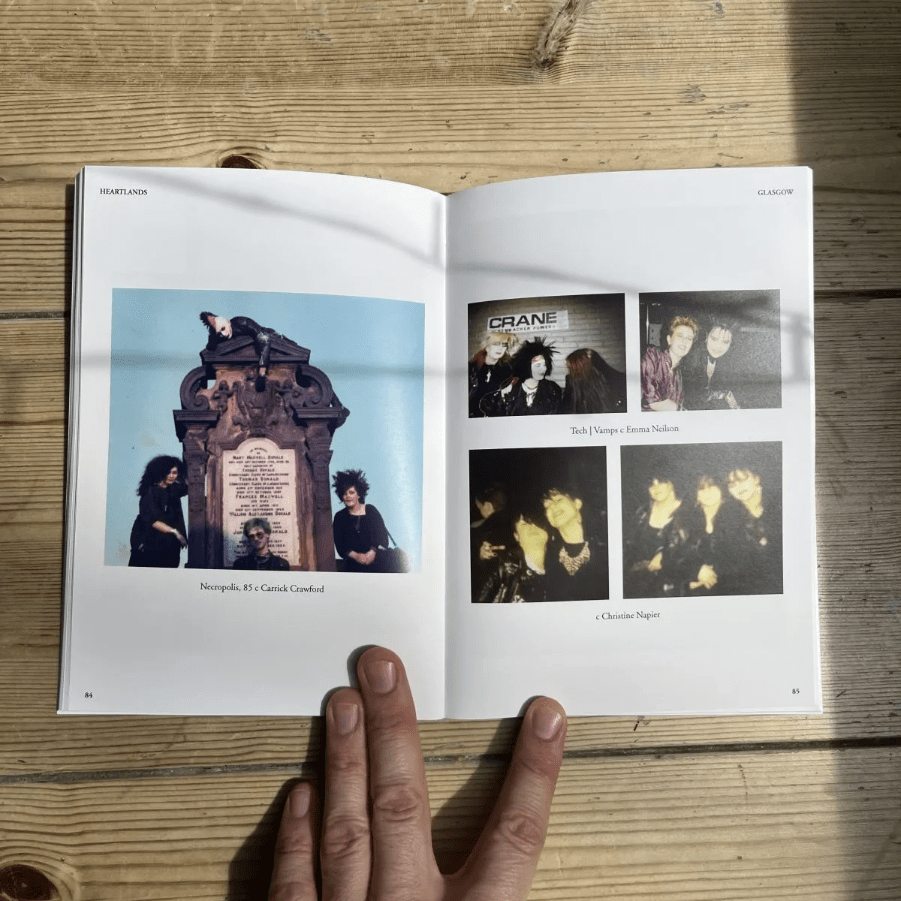

“Going to clubs like Night Moves, aged 17, was a thrill,” says Chris Brickley. “Some of the people were a real spectacle. Arty, expressive. I recall a guy with a half-shaved long Mohican haircut, wearing two kids’ pistol holsters across-ways, with a banana in each instead of toy guns.”

Chris explains that those engaged in the early goth scene were first and foremost experimental in their approach to fashion. Surely the DIY hairstyles referenced would have been inspired by the punk scene of the time, although goth often had no qualms about adopting similar Avant Garde haircuts.

Image Credit: Chris Brickley, Heartlands

The life cycle and cultural output of the original goth and punk movements of the United Kingdom have been documented by many social historians and physical/digital archivists. ‘Heartlands’ by Chris Brickley is one such archival photobook that documents the Glasgow goth scene, in its original incarnation during the 80’s. The book exemplifies how those involved in the early local scene were practicing a do-it-yourself fashion ethic.

I take Brickley’s work here as an example because his work covers Glasgow’s local scene – a scene close to home.

Goth as depicted in the photobook is indeed very diverse, but there are commonalities between the photographs included. These include the diverse forms of expression found in goth fashion, with irregular jewellery and clothing abound. The photobook documents many different people coming together to co-create a certain type of atmosphere.

The Gothic and archived material relating to the goth subculture also places a heavy emphasis on the politics of space and place. The goth subculture is often keen to explore green spaces, such as graveyards or forests which are home to trees and vegetation. Glasgow is a highly urbanised and industrialised city, with green spaces becoming increasingly rare. Indeed, across much of urban living there is generally a distinct lack of greenery.

The scene in effect transforms darker, less conventional places into third spaces, where one can be in closer proximity to their ‘ecological self’. This is to say, one is closer to experiencing life outside of rampant industrialisation. This escape would allow for self-actualisation through recreation in goth spaces.

Image Credit: The Cure ‘A Forest’

Post-punk and new wave are music genres that embody both collectivist and individualistic notions. Like punk music, much of the yearning as seen in the gothic music genre was directed at personal problems and grievances turned outward. This allowed for the personal to be connected to the political. Fears of a changing world, isolation and ecological decline were and still are represented within the music genre.

The mood and tone of goth as a music genre did however differ from punk in one keyway. Instead of anger as the primary emotion, sadness and melancholy prevailed. While punk expresses a distinct anger towards authority in all its destructiveness, goth creates a space for people to mourn and grieve of a future that was once promised to them but seems all too far away.

As mentioned before, science-fiction is a mainstay for Gothic literature. Within the Gothic, there is a tendency for authors to blur the lines between ‘human’ and ‘animal’. This is often done through use of physical metamorphosis – the protagonist or other characters become or are vampires, werewolves, or something else belonging to the category of ‘other’.

Scholars such as Bob Curran have put forth the notion that werewolves as a literary construct have their roots in tales of people inhaling plants such as wolfsbane. In Bram Stokers Dracula, Dracula himself occupies the ‘other’ and his vampirism evokes strong anxieties for those situated within human society.

Both vampirism and lycanthropy alike have ties to the lunar cycles and thus natural processes to exist. Moreover, this proximity to nature further blurs the lines between the human and the animal.

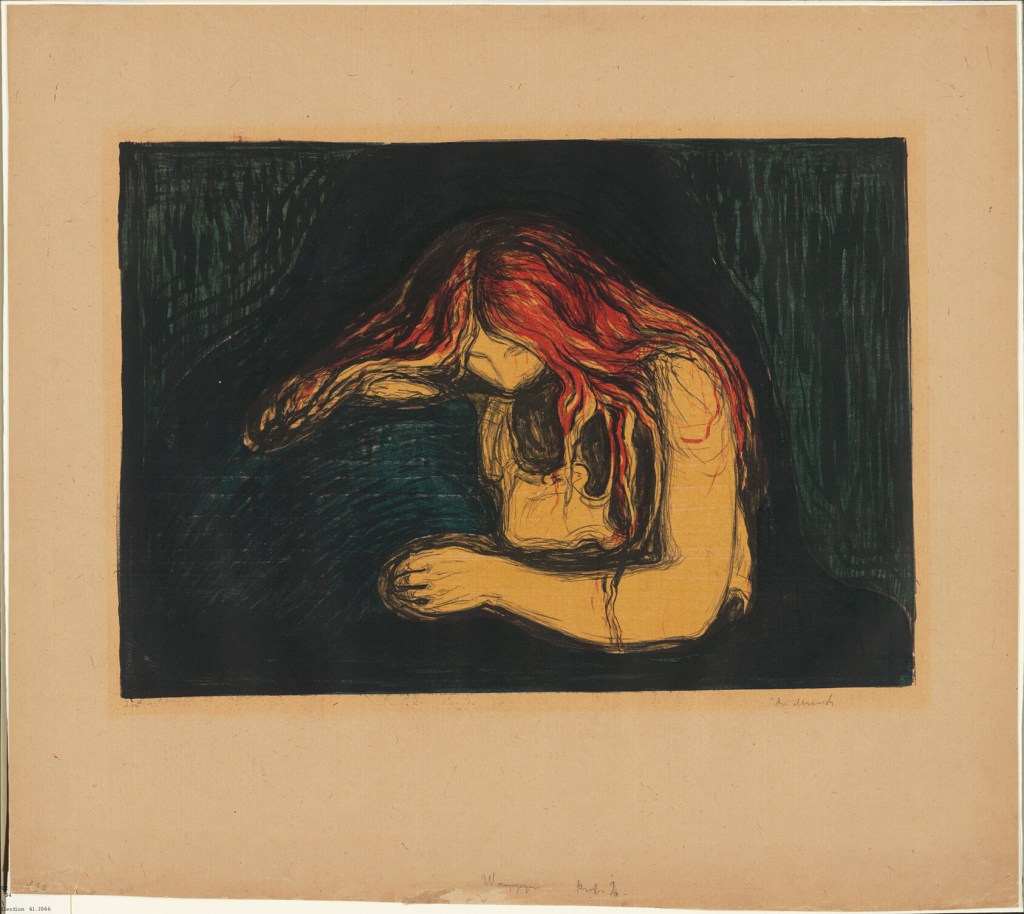

Image Credit: ‘The Vampire II’ Edvard Munch 1895-1902

The vampire and lycanthrope literary categories serve a particular purpose in dissolving the human-nature binaries as set up by society. Dracula’s ability to infect others with the vampiric curse is often correctly read as commentating the spread of disease in Victorian Britain. However, it is also possible to read Dracula as commentary on the relationship between humankind (as a politically constructed category rife with racial and gendered expectations) and the ‘other’.

In the collection of essays entitled ‘Lunar Gothic’, Patrycja Pichnicka-Trivedi explains: “This idea of similarity and difference creates a necessary dynamic in the relationship between the vampire, the slayer, and the victim. The victim is similar and yet different from both vampire and slayer, being prone to the influence of both.”

The celebration of these human-animal transformations continues to be commonplace within the goth subculture. Many of those who enjoy gothic fashion freely and openly straddle this human-animal binary with the use of costume, makeup and accessories.

Mary Shelley herself was inspired by ecological modes of thought when she wrote Frankenstein. Vegetarianism (and at times in her life, veganism) heavily inspired Mary Shelley’s work.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Using this particular lens, Shelley deliberately portrayed Frankenstein’s monster as both human and nonhuman, female and male, civilized and savage. This portrayal functions once again as a way to investigate the validity of societal structures that portray this ‘uncivilization’ and nature itself as humankind’s problem to be solved. Instead, an equilibrium with the societal ‘other’, nature and animals is posed as a better alternative.

An Eco-Goth Revival?

Many feel dismayed that their favourite subculture has been commodified to such an extent that it no longer seems familiar. However, all is not lost.

One key way that can reconnect to the subculture in a non-commodified is through literature. There are many free PDFs online of both new and classic Gothic novels that emphasise the original boldness of the genre and the ideas it contains even to this day.

Moreover, although DIY has declined in some spaces there is still a way for communities to come back together to embrace this ethic. Making or collecting sew-on patches from merch stalls, friends or through a band’s Bandcamp account can be a good way of connecting with the scene and working towards a more do-it-yourself approach to fashion. Sharing these creations with others is also important to make DIY a more visible practice.

Divesting from fast fashion and embracing second-hand clothing (as the original goth communities were often keen to do) is another important way of reconnecting with one’s ecological self.

Image Credit: Mayara Caroline Mombelli / Pexels

It is entirely possible to forge a more constructive and contemplative goth subculture – one that harmonises itself with nature during ecological downturns. Subcultures such as these can be resilient against the rising tides of political instability across the world.

Due to the intra and extra-communal exchange that is commonly associated with DIY culture, many of those who exist within the goth scene embrace subcultural fluidity. In this way, the goth subculture openly embraces fluidity more broadly, freedom and the dissolution of rigid social categories.

Featured Image Credit: Misty Postcard, n.d